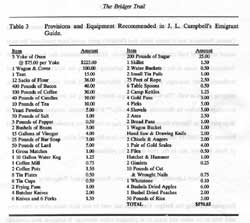

|

After

making the initial decision to pull up stakes and leave familiar

surroundings, emigrants traveling to the gold diggings in Idaho

and Montana in the early 1860s still had to make serious decisions

regarding the type of outfit to put together. Should they use horses, mules, or oxen? What type of equipment would they use, and

how much and what type of provisions should they stow in the wagon

for a trip that could take up to four months to complete? It was

thought that important accouterments for a successful trip included

a trail diet that prevented scurvy, essential provisions to last

until harvest the following year after arriving at their destination,

and sufficient firearms and ammunition. To aid the emigrant unfamiliar

with trail travel across the plains, several emigrant guidebooks

had been published since 1848 by Mormon emigrants and California

gold rushers alike. These included a new guidebook published in

time for spring departures in 1864. An example of recommended equipment

and provisions is provided in the Table.

horses, mules, or oxen? What type of equipment would they use, and

how much and what type of provisions should they stow in the wagon

for a trip that could take up to four months to complete? It was

thought that important accouterments for a successful trip included

a trail diet that prevented scurvy, essential provisions to last

until harvest the following year after arriving at their destination,

and sufficient firearms and ammunition. To aid the emigrant unfamiliar

with trail travel across the plains, several emigrant guidebooks

had been published since 1848 by Mormon emigrants and California

gold rushers alike. These included a new guidebook published in

time for spring departures in 1864. An example of recommended equipment

and provisions is provided in the Table.

The type of team and wagon to chose

was one of the most important decisions that  had

to be made, and one that required serious consideration. By the

early 1860s, there were several companies in the East that had

experience making wagons for rugged travel across the plains and

mountains. Still, even wagons constructed with the best craftsmanship

and hardwoods often broke down under the rigorous demands of western

trail travel. The wagons made in the 1860s were hybrids of the

original Conestoga wagon developed in the eighteenth century by

the Pennsylvania Dutch. Two of the most popular makes of wagons

were manufactured by Joseph Murphy's company in St. Louis, and

those made by the Studebaker brothers in South Bend, Indiana.

These were preferred for overland emigrant travel versus larger

models such as the Carson wagon used in heavy freighting. The

Murphy and Studebaker wagons were custom made according to individual

owner specifications, and could cost from $500 to $1,000. The

Studebakers advertised that a member of the company had travelled

west and therefore knew how to build wagons for emigrants. The

Stanfields and Bartletts were family friends of the Studebakers.

For Howard Stanfield, it was only natural that he headed west

in a Studebaker wagon. had

to be made, and one that required serious consideration. By the

early 1860s, there were several companies in the East that had

experience making wagons for rugged travel across the plains and

mountains. Still, even wagons constructed with the best craftsmanship

and hardwoods often broke down under the rigorous demands of western

trail travel. The wagons made in the 1860s were hybrids of the

original Conestoga wagon developed in the eighteenth century by

the Pennsylvania Dutch. Two of the most popular makes of wagons

were manufactured by Joseph Murphy's company in St. Louis, and

those made by the Studebaker brothers in South Bend, Indiana.

These were preferred for overland emigrant travel versus larger

models such as the Carson wagon used in heavy freighting. The

Murphy and Studebaker wagons were custom made according to individual

owner specifications, and could cost from $500 to $1,000. The

Studebakers advertised that a member of the company had travelled

west and therefore knew how to build wagons for emigrants. The

Stanfields and Bartletts were family friends of the Studebakers.

For Howard Stanfield, it was only natural that he headed west

in a Studebaker wagon.

A custom crafted wagon might be more

comfortable and better designed for storing items and sleeping, but a basic farm wagon of simple design often

proved to be easier to dispose of once emigrants reached their

destination, where, by selling equipment they no longer had use

for, they could raise the capital necessary to begin establishing

winter quarters. In his 1864 guide book, J. L. Campbell suggested

that, "As to a wagon, it does not require an expensive one;

just such a one as a farmer would select to do his farm work (a

common lumber wagon) is the most suitable. This kind will meet

with ready sale in the mines, whereas more expensive wagons with

springs and stationary covers are in less demand." As Campbell

suggests, many emigrants used ordinary, and in many cases, homemade

wagons.

items and sleeping, but a basic farm wagon of simple design often

proved to be easier to dispose of once emigrants reached their

destination, where, by selling equipment they no longer had use

for, they could raise the capital necessary to begin establishing

winter quarters. In his 1864 guide book, J. L. Campbell suggested

that, "As to a wagon, it does not require an expensive one;

just such a one as a farmer would select to do his farm work (a

common lumber wagon) is the most suitable. This kind will meet

with ready sale in the mines, whereas more expensive wagons with

springs and stationary covers are in less demand." As Campbell

suggests, many emigrants used ordinary, and in many cases, homemade

wagons.

Oxen were the draft animals most

commonly used on the northern plains and intermountain region

by large freight companies such as Russell, Majors, and Waddell.

Oxen were less expensive, required less feed, and were less likely

to stray or be stolen by Indians. However, many emigrants used

horses or mules as their team of choice.

As his train was about to depart the Bridger Trail cutoff, Ethel

Maynard noted that there were "about 100 wagons more horse

and mule teams than there were of ox teams."

Horses and mules moved along the

trail at a faster pace than oxen. In several places, Maynard wrote

that those travelers with horse and mule teams wanted to  continue

on, rather than wait for the slower, but sure-footed oxen. As

his train descended the Bridger Mountains, "It was some trouble

for the train to keep together as the horse and mule teams wanted

to go ahead and would travel a little faster than the cattle [oxen]

But they did not feel safe to leave the train that is those who

had cattle. . . ." The Bighorn River crossing "divided

our train as the horse teams got over first and went on and left

the cattle men. We did not get our wagon over until the second

day." continue

on, rather than wait for the slower, but sure-footed oxen. As

his train descended the Bridger Mountains, "It was some trouble

for the train to keep together as the horse and mule teams wanted

to go ahead and would travel a little faster than the cattle [oxen]

But they did not feel safe to leave the train that is those who

had cattle. . . ." The Bighorn River crossing "divided

our train as the horse teams got over first and went on and left

the cattle men. We did not get our wagon over until the second

day."

Charles Baker kept a record of the

purchases he made as he outfitted himself for the trip to Montana. He kept a rough ledger account record in his

diary that showed the price of various equipment, commodities,

and merchandise available in the Mid-western

United States during the 1860s. Baker purchased his initial supplies

for the trip to Virginia City between March and May, 1864 for

approximately $310. All of the articles, the quantity, price,

and date of purchase are given in the Table.

trip to Montana. He kept a rough ledger account record in his

diary that showed the price of various equipment, commodities,

and merchandise available in the Mid-western

United States during the 1860s. Baker purchased his initial supplies

for the trip to Virginia City between March and May, 1864 for

approximately $310. All of the articles, the quantity, price,

and date of purchase are given in the Table.

|

|